Twenty-five years ago, British diplomat Robert Cooper published a short pamphlet called The Postmodern State and the World Order. Widely accepted as a strategy for the times, it argued that the “modern” geopolitical era in Europe was giving way as globalization and the collapse of the Soviet Union removed the need for the modern state. In its place, Cooper foresaw the emergence of a “postmodern bloc” of nations—largely coterminous with the European Union—which interfered with national laws, “right down to beer and sausages.”

Cooper did not think the post-Cold War world would be without its troubles, however. Just as the collapse of the Soviet Union and globalization were removing the need for the modern state, they were also destabilizing a number of fragile countries, to the extent that “zones of chaos” were emerging around the world—and particularly in the former Yugoslavia. For Cooper, as for other leaders at the time, Europeans would need to do more to stabilize these countries, even mandating a kind of “liberal imperialism.” Serving from 2002 to 2010 as director general of politico-military affairs at the General Secretariat of the Council of the EU, Cooper helped shape the EU’s 2003 European Security Strategy, and European strategic discourse more broadly.

Fast forward to 2025 and the world—particularly Europe—looks very different. A large, opportunistic state to the east of the continent, Russia, is waging war against another large European state, Ukraine, in a way that few analysts would have thought possible only a few years ago. Another powerful state to the northwest of the continent, the United Kingdom, has withdrawn from the EU, putting paid to one version of Cooper’s vision of geopolitical postmodernity. And while NATO has welcomed some new members in Sweden and Finland, a number of both NATO and EU member states—from Hungary and Slovakia to Turkey and possibly Austria—have started to act like “cuckoos in the nest.” They have flirted with the Kremlin or charted their own courses.

For all the talk of EU “strategic autonomy,” it was British and American intellectual leadership, intelligence, and military-organizational muscle which informed Europe in late 2021 of Russia’s intentions to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, shored up Ukraine in early 2022, and enhanced deterrence along NATO’s eastern front. It was to the UK, not the EU, that Finland and Sweden looked to provide security assurances once they decided to abandon neutrality in the face of an imminent threat. In short, the “old world” is looking decidedly “modern” again, while the “new world,” especially the United States, will no longer offer Europeans a free ride.

Geopolitics Intensifies

So, what did early 21st century European strategists get so wrong? To be fair, they got a lot right. Cooper, for example, counselled that Europeans would still need strong defenses to deter rivals and subdue enemies, writing in 2000 in The Postmodern State: “Among ourselves, we keep the law but when we are operating in the jungle, we also must use the laws of the jungle. In the coming period of peace in Europe, there will be a temptation to neglect our defenses, both physical and psychological. This represents one of the great dangers for the postmodern state.”

Unfortunately, the need for strong defenses was ignored, while geopolitics was largely dismissed as obsolete. Europeans treated countries such as Russia and China as “democracies to come,” even when it became clear those countries had other plans. Far from becoming “responsible stakeholders” in the open international order, Moscow and Beijing became aggressive competitors and then hostile adversaries.

At the time of Cooper’s writing, China was little more than a geopolitical minnow, having witnessed a near revolution in Tiananmen Square only 11 years before. After decades of economic growth and modernization, today China possesses the world’s largest manufacturing capability, shipbuilding industry, and merchant marine. China is now being drawn into the world: The country secures energy from the Middle East and Western Africa, buys resources from Africa and South America for economic modernization, and sells its manufactured goods to consumers in Europe and North America. Indeed, those behind the so-called Belt and Road Initiative have their gaze fixed firmly on Western Europe.

Already in possession of the world’s largest fleet, Beijing is developing the capacity to project power over extensive distances; it won’t be long before Chinese vessels or even flotillas make frequent visits to European peripheries, adding to the continent’s complicated maritime flanks. The Chinese navy, once a minnow, is now a shark.

Implications of the New Geopolitics

British and continental European strategists have only recently started to realize how serious and entwined the implications of the new geopolitics are. Russia’s war against Ukraine has drawn China, Iran, and North Korea into Europe. North Korean troops are thrown at Ukrainian positions, Iranian drones bomb Ukrainian targets, and Chinese economic, industrial, and technological support keeps Russia afloat.

True, China, Iran, and North Korea may have little direct interest in a Russian victory, but they see great danger in a Russian defeat. Should security in Europe improve, the UK and EU member states would be freer to project themselves into the Indo-Pacific. By distracting Europeans—and Americans—in Eastern Europe, Beijing, Tehran, and Pyongyang are reducing the Euro-Atlantic democracies’ ability to constrain Chinese, Iranian, and North Korean interests in the South China Sea, in the Middle East, and the Korean peninsula, respectively.

So, while these so-called CRINK countries—China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea—may not like one another, they are all bound by a scorn for the democracies, and not only the US. Russia’s war against Ukraine may be the first Indo-Pacific proxy struggle. Whisper it, but Europe is no longer the geographical pivot of history; it is now little more than a periphery of affairs in the Indo-Pacific.

Sea Power and Europe’s Maritime Flanks

When considering geopolitical realities, it’s often helpful to look at a map or, better still, a globe. Europe’s front line against its nearest adversary—Russia—is certainly the land frontier to the east of the continent, but its northern and southern flanks are decidedly maritime. To hold a strong front, it should go without saying that Europeans need to protect their flanks. Not only should they guard against losing command over maritime regions such as the Arctic Ocean and the Baltic, Mediterranean, and Black Seas, but it is in these spaces where Europeans can seize the initiative and double-down on outflanking their rivals.

One of the most strategically important events of recent tumultuous months has been Russia’s temporary, hopefully permanent, loss of a naval foothold in the Mediterranean (Tartus), with its consequent implications for the Kremlin’s ability to project power and support client actors, particularly in Africa. For the first time in decades, there is no easy way for Russia to make its presence felt in the Mediterranean—Europe’s “soft underbelly.”

Meanwhile, in the north, the opening of new sea routes between east and west and the increasing accessibility of natural resources will, over time, be an economic game-changer. It is not in Europeans’ interest to allow Russia to turn the Northern Sea Route into a “national toll road,” nor allow the non-Arctic Chinese to become the High North’s principal economic beneficiary. It is not only Russia’s littoral zones that should spark European interest. There are sound geopolitical and security reasons for US President Donald Trump to make noises about Greenland and Canada.

Most importantly, Europe’s economies, as they always have, depend on seaborne trade amongst themselves and their neighbors, but especially with the ever-growing Indo-Pacific markets. As map 1 shows, the military reinforcement of mainland Europe, should one be needed, will come by sea, as it did in World War I and II, as well as the Cold War. If non-state or proxy actors can effectively eject Russia from the Mediterranean or close a shipping channel key to global trade, it’s hard to conceive of the damage a more powerful rival could do.

The Houthi actions in the Bab-el-Mandeb have done their damage, but at least there is an alternative route. Consider the economic implications of Iran closing the Strait of Hormuz, or of China imposing a blockade on Taiwan. Similarly, in the information age, it’s important to remember that the bulk of global data travels through subsea cables, cables susceptible to action as simple as a ship of the shadow fleet dragging its anchor for a few miles.

NATO’s name is no accident. The geographical reference in its title is an ocean; an ocean that bounds together the mutual interests of friends and allies. But with the eastward shift in the world’s economic center of gravity, the westward movement of China’s interests, climate change-driven alternatives to navigation, and technological advances, which both lower the barriers to entry for actors in the maritime environment and introduce new vulnerabilities, NATO allies can no longer limit their security concerns to a single geographical area.

A New Geostrategy to Respond to the CRINK

In the new geopolitical age, it would be convenient to embrace the confection that Americans, Japanese, and Australians should tend the Indo-Pacific and Britons and other Europeans the Euro-Atlantic. But this would be intellectually lazy, not least because of the growing alignment between the CRINK countries, to which the democracies need an answer.

The UK’s “Integrated Review Refresh,” published in March 2023, was the first national strategy to publicly recognize that the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters are being drawn together. It was also the first to embrace deepening these linkages, especially between the leading democratic powers. Only by working together to uphold an international order based on openness, clear rules, and mutual interests can security be upheld and aggressors resisted. For all its might and power, the US cannot take on this burden alone, nor does it want to. Trump may not be an outlier, but instead representative of a new breed of American politician clear in the need to pursue the national interest—and in a narrower and more transactional sense.

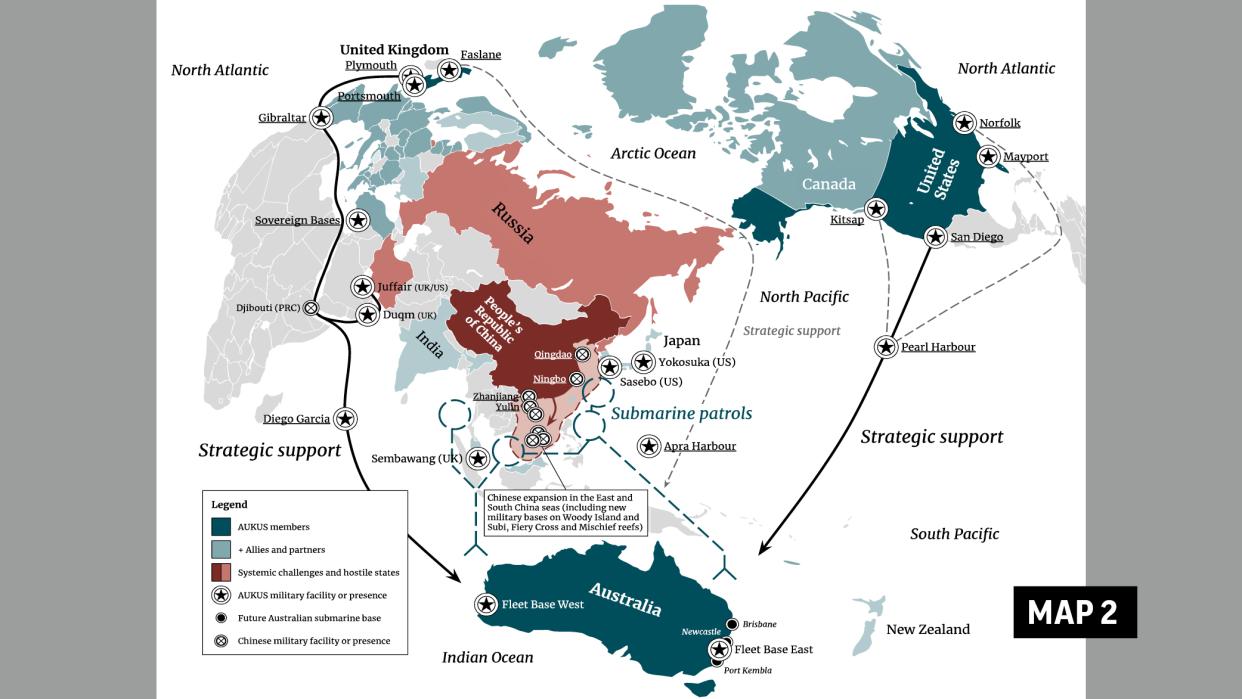

The UK, Japan, and certain European countries are beginning to act, as shown on map 2. AUKUS, the seminal trilateral initiative by Australia, the UK, and the US to provide Canberra with nuclear-propelled submarines and accelerate technological development in high-impact areas, and GCAP, the British, Japanese, and Italian sixth-generation fighter project, are the most obvious examples of new security ties designed to bridge both theaters. There are older connections, too, such as France’s sovereign presence in the Indo-Pacific and the UK’s historic links kept alive through defense pacts such as the Five Power Defense Arrangements, tying together Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK.

These links should be reinforced. The sequencing of Italian, French, and British carrier strike group deployments to the Indo-Pacific and national deployments—such as Germany’s—should continue. The Royal Navy will deploy another carrier strike group as far east as Japan and South Korea in mid-2025, which will include at least two other European vessels (from Norway).

But this is not enough. To maximize their potential, the democracies—particularly in Western Europe—should invest more in defense. For the UK the average spending on defense from 1950 to 1990 was 6.4 percent of GDP, while it was 3.4 percent for (West) Germany, and 4.3 percent for France. This makes recent concern over the possibility of reaching 2.5 percent of GDP look like a debate over small change.

European NATO states on the continental frontline understand what is at stake—the Polish, Finnish, and Baltic focus on defense is to be applauded. Those maritime states working the flanks should do likewise. A serious increase in investment in defense can be realized; it just requires political leadership and a clear explanation to the public as to why it is needed. Trump, for his own reasons, is starting, once again, to shine a light on the issue. Germany, Italy, Spain, and France—even the UK—cannot continue to shirk. Without strong defenses, the CRINK will not be deterred, making the risk of war more, not less, likely.

Relearning the Art of Geopolitics

In today’s world, Europeans need to relearn the art of geopolitics. They have an existing advantage in their deep-rooted mutual interests and network of alliances, including the most successful military alliance ever—NATO. But this is not the time for complacency; threats and challenges come increasingly from the Indo-Pacific, be they from state, non-state, or economic quarters.

No single country can do it all alone, which is why even the US needs help. To prevent the CRINK from seizing the initiative in the 2030s, Europeans need to rebuild and expand their defenses. While the deterrence of aggressors along the continental front will remain central, the maritime approaches and flanks of Europe cannot be ignored.

James Rogers is co-founder of the Council on Geostrategy in London. Kevin Rowlands is head of the Royal Navy’s Strategic Studies Centre and associate director of the Sea Power Laboratory at the Council on Geostrategy. He writes strictly in a personal capacity.